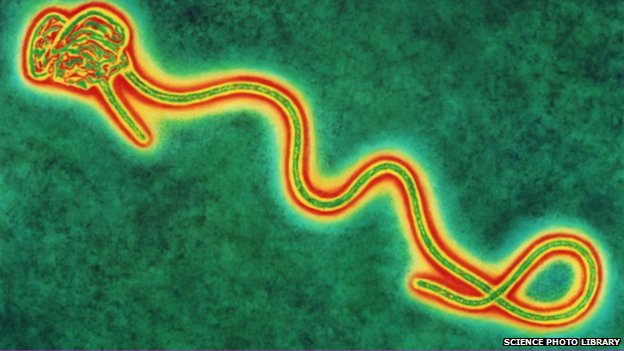

In what seems like a rollercoaster ride of news and pronouncements concerning the 2014 Ebola outbreak, we have been told not to worry,  it is a fragile virus that does not move easily between host and victim, it is not airborne, the US healthcare system can easily contain an outbreak through better infection control process and modern healthcare provision. And we have an experimental vaccine ready for human trial, and several more in the pipeline. These were all used to justify bringing infected aid workers into the country, and the CDC’s and NIH’s horrible track records notwithstanding, it is probably true that Emory’s specially-designed isolation program can contain the chain of transmission here in the US. But that only proves we can contain the disease here under the best circumstances.

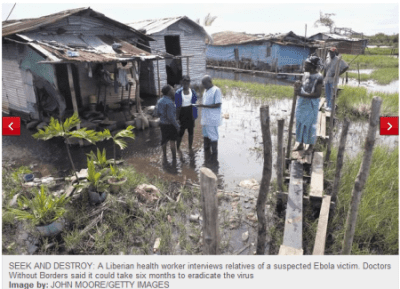

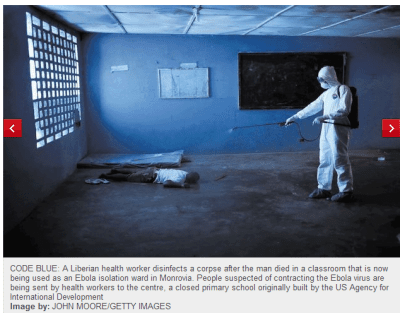

On the other hand, we are being told by people on the ground (MSF & WHO) that the outbreak is a runaway train plowing through the country side, fueled by fear of treatment, overwhelmed authorities and entrenched cultural practices. Recent photos from Monrovia Liberia, where gunmen ransacked a quarantined clinic, looted it of contaminated items and equipment and scattered known and suspected patients into the surrounding slums do not bode well; the virus spreads through direct contact with human fluids and waste and the wet, muddy, flooded environment is a perfect vector for waterborne illness. To date the death toll in Africa has reached over 1,200 according to the New York Times. Meanwhile, reports on how the repatriated Americans who received the experimental drug are progressing have been few and far between.

On the other hand, we are being told by people on the ground (MSF & WHO) that the outbreak is a runaway train plowing through the country side, fueled by fear of treatment, overwhelmed authorities and entrenched cultural practices. Recent photos from Monrovia Liberia, where gunmen ransacked a quarantined clinic, looted it of contaminated items and equipment and scattered known and suspected patients into the surrounding slums do not bode well; the virus spreads through direct contact with human fluids and waste and the wet, muddy, flooded environment is a perfect vector for waterborne illness. To date the death toll in Africa has reached over 1,200 according to the New York Times. Meanwhile, reports on how the repatriated Americans who received the experimental drug are progressing have been few and far between.

Most experts agreed early in the outbreak that the best strategy to contain a potential pandemic was to stop it at the source and prevent it from being transmitted from one country to the next. Unfortunately, that became very difficult as the disease spread to urban areas and then showed up in Nigeria, the most populated country in the region. CDC has reportedly allocated ~350 personnel to help prevent the spread by send over 50 to Africa, supported by another 300 back in the US, according to an 8/13 CDC Press Release:

“CDC currently has 55 people deployed to West Africa to fight Ebola’s spread: 14 in Guinea, 18 in Liberia, 16 in Sierra Leone, and seven in Nigeria. While the number of CDC experts may change slightly from day to day, given staff rotations, more than 60 CDC personnel are expected to remain in these four countries continuously.“

At this point, we can hope that the CDC’s efforts and support will be able to break the chain of transmission as one part of the equation, though it will be tough; in addition the 21-day asymptomatic incubation period of the disease and the possibility of transmission through sexual intercourse up to six weeks after being treated and asymptomatic. As late as today, the Associated Press and ABC reported that air travel is less dangerous because it does not involve the kind of close contact that spreads the disease. We beg to differ: Although the virus may not spread alone as an airborne agent, one sneeze and a subsequent drink in the next seat, or a subsequent cup collection followed by a touch to the eyes or mouth can spread the virus; viruses have evolved to infect this way.  And like dysentery and cholera, the fecal-oral route is a major contributor to the spread and this possibility is higher than some would have us believe.

At this point, we can hope that the CDC’s efforts and support will be able to break the chain of transmission as one part of the equation, though it will be tough; in addition the 21-day asymptomatic incubation period of the disease and the possibility of transmission through sexual intercourse up to six weeks after being treated and asymptomatic. As late as today, the Associated Press and ABC reported that air travel is less dangerous because it does not involve the kind of close contact that spreads the disease. We beg to differ: Although the virus may not spread alone as an airborne agent, one sneeze and a subsequent drink in the next seat, or a subsequent cup collection followed by a touch to the eyes or mouth can spread the virus; viruses have evolved to infect this way.  And like dysentery and cholera, the fecal-oral route is a major contributor to the spread and this possibility is higher than some would have us believe.

Forbes points out that the CDC has the ability to quarantine and the rules concerning this very broad authority are not as clear as they should be. Before it becomes necessary to actually implement a quarantine that would potentially keep many people isolated for months against their will, especially in the current political environment, it may be advisable to consider some travel restrictions (or very credible screening for air travellers) from countries that are currently in the throes of an outbreak.

Forbes points out that the CDC has the ability to quarantine and the rules concerning this very broad authority are not as clear as they should be. Before it becomes necessary to actually implement a quarantine that would potentially keep many people isolated for months against their will, especially in the current political environment, it may be advisable to consider some travel restrictions (or very credible screening for air travellers) from countries that are currently in the throes of an outbreak.

0 Comments